While we must plan for success in owning and operating an equine business, everyone knows that horses can often bring the unexpected. To avoid unforeseen legal pitfalls, equine business owners must take care to avoid these common legal mistakes.

1. Failure to Use Contracts

The importance of using contracts in connection with your equine business cannot be emphasized enough. While it may seem repetitive, a many equine business owners still shy away from using contracts for fear of putting-off, losing clientele, or incurring time and costly expenses in drafting and maintaining these documents.

However, the reality is:

- Clients who prefer to avoid contracts typically do not make good clients because they do not want to make the commitment to following rules and may be averse to abiding by your procedures; and

- Failing to expend needed time, effort, and money to protect and best position your burgeoning horse business is short sighted because it may cost you more down the road if a lawsuit is filed or a tax audit ensues.

When waffling whether to use contracts, consider whether your business can afford a legal battle down the road that may impact your financial resources, your operation, and business reputation. While sometimes unpleasant, contracts force you to anticipate what may go wrong with your business and best position you in the event of a disagreement or incident. The best way to avoid confusion and achieve clarity as to your rights and responsibilities is to have agreements in place.

While contracts do not prevent a lawsuit from occurring, the beauty of written agreements is that after a lawsuit is filed and the parties are amidst litigation, a court cannot after-the-fact rewrite the terms of the agreement – they are what they are so make sure they are written well.

Common agreements include, among others:

- Boarding agreements

- Liability releases (for both boarders and guests)

- Trainer agreements with any trainers giving lessons at your barn. This contact ensures that the trainer will indemnify you for any accidents that occur at your barn and provide that the trainer is not an employee.

- Finally, consider drafting farm rules that are part of any boarder’s contract with you.

In addition to barn or business specific provisions, clauses to look at in your contracts include, but are not limited to:

- choice of law and/or venue clause (if there comes a time when there is a dispute and a lawsuit is filed, where do you want to litigate the action);

- arbitration provisions (do you want to be able to avoid costly and time consuming court litigation and require parties to undergo arbitration, often a more streamlined process);

- attorneys’ fees (if there is a dispute and a lawsuit follows, will each party bear their fees/costs with the lawsuit or will the prevailing party’s fees/costs paid by the losing party);

- indemnification provisions (is one party required to indemnify another party if a claim is filed and/or does the agreement allow for indemnification in the event of one’s own negligence).

Even if you are working with an attorney, read, review, and update your contracts annually, as needed. As your business changes, make edits as needed. There also may be changes or updates in the law.

Finally, keep in mind that contracts may be subject to your specific equine business needs, as well as state specific issues and/or laws. If the agreements are complex, do not hesitate to seek help from a knowledgeable attorney.

2. Misclassification of Employee

There is often much confusion on whether an employee is considered an “independent contractor” or an “employee” in the eyes of the law. Classification matters because it may materially impact insurance and liability issues.

Business owners may prefer to classify employees as “independent contractors” because an owner who employs an independent contractor is not liable for injuries to third persons caused by the contractor’s negligence. (I) Generally, to receive worker’s compensation benefits under a state worker’s compensation act, a worker must have been an employee of an employer subject to the act at the time of the injury.

IRS guidelines and case law provide guidance as to some of the factors to be considered by evaluating whether a person is an independent contractor. As an example, case law provides the following four factors when assessing whether an individual is an “independent contractor”:

- Selection and engagement;

- Payment of compensation;

- Power of dismissal; and

- Power to control the work of the individual. (ii)

The fourth, the power to control, is often a determinative factor. This refers to control over the means and method of performing the work. In making these determinations, the courts will look to the “totality of the circumstances of the work” and examine various “indicia of control”. Worth noting is that courts often find that it is immaterial whether the employer actually exercises this control; the test is whether the employer has the power to exercise such control. (iii).

For example, courts have held an exercise rider to be an employee rather than an independent contractor despite a trainer’s claim that the rider was an independent contractor. For example, the court identified the following factors to establish sufficient indicia of control: (iv)

- lack of freedom to seek out other business opportunities – the exercise rider only exercised horses for other trainers with permission of trainer and when finished work for trainer;

- provision of “tools” – the trainer provided the horses, saddles, and bridles and all the equipment necessary for his stables; exercise rider provided his own helmet, whip, chaps, boots, and vest;

- subject to the business’ instructions – with regard to the extent that trainer could control the details of exercise rider’s work, trainer posted a list of horses at the barn and detailed what type of work should be done by the exercise rider with that horse, i.e., jog, break, gallop, etc.

As a further example, Virginia case law provides:

“An independent contractor is a person who is employed to do a piece of work without restriction as to the means to be employed, and who employs his own labor and undertakes to do the work according to his own ideas, or in accordance with plans furnished by the person for whom the work is done, to whom the owner looks only for results.” (v)

In other words, are you controlling how your worker gets the job done or just looking to whether the job gets done? If a contract is involved, check whether the contract with this individual explicitly states that he/she is not an “employee” of the farm. Unfortunately, this determination is not a “bright-line rule” but rather, nuanced and employing a multi-factored analysis subject to case-by-case assessment. (vi)

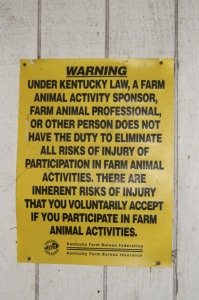

3. Not knowing the requirements of your state Equine Activity Liability Act (“EALA”)

Despite the fact that many states now have in place an EALA this does not mean “zero liability” and that you should not be concerned about being liable or getting sued. Even the individual with the tightest agreement can get hauled into court. Despite a state EALA, you still should have the appropriate insurance in place and have farm animal activity participants sign equine activity release and hold harmless agreements. Make sure that parents or guardians sign for minors. Make sure to tailor the language in these agreements depending on your operations. Envision different scenarios and tailor the language in your agreements to address different types of “participants” – e.g. someone who is riding versus visiting the farm and use terminology to protect yourself from more than incidents occurring while on horseback.

For example, potential dangers that you may want to be held harmless from could include those occurring in mounting, riding, walking, handling, boarding, feeding horses, or visiting the horse farm (what about the friend of a friend who is visiting and has never been around horses?).

Further dangers could involve interactions with the horse that person is riding or visiting, another horse, or another animal altogether. (As an example, a farm that also raises sheep). Also consider adding language that horses by their very nature can behave unpredictably and can among other things, spook, buck, rear, bit, kick and break loose from handlers for other enclosures. The more inclusive the language, generally the better.

4. Failure to obtain the proper insurance.

State equine activity liability act laws do not prevent you from getting sued. As an equine business owner, you must obtain the proper liability insurance depending on your equine business activities and depending on your operations. Check with your insurance agent and read your policies to determine what is being covered. Your homeowner’s policy likely does not cover business pursuits so make sure to obtain a policy that does – a commercial general liability insurance policy, “care, custody, and control” insurance, an umbrella policy, and potentially worker’s compensation insurance depending on your business operation and state requirements. Provided statutory requirements are met and absent some circumstances, your state worker’s compensation act will provide the exclusive remedy for an employee injured on the job – also known as the “worker’s compensation bar.”

For example, when an employee in Virginia is injured in the performance of her duties for her employer, the Virginia Workers’ Compensation Act provides her sole and exclusive remedy against the employer. (vii) Therefore, an employee will be precluded from maintaining a common-law action (e.g. negligence) against his employer for an injury sustained in the course of employment when he and his employer have accepted the provisions the provisions of the act.

5. Not understanding tax implications

As you set up your business, you need to keep in mind the tax implications of your business. After incorporating your business, you will be responsible for corporate taxes in the state where you are incorporated. The deductibility of taxpayer expenses related to an activity depends on whether it is carried on for profit. (viii) Subject to certain exceptions, a person may not deduct a loss attributable to an activity unless that activity is engaged in for profit. (ix) For example, a taxpayer may not deduct losses related to an activity carried on primarily as a sport, hobby, or for recreation. (x)

An activity is engaged in for profit if the taxpayer has an actual, honest profit objective, even if it is unreasonable or unrealistic. (xi) IRS regulations include a non-exhaustive list of nine factors to consider in determining whether a business is engaged in for profit:

Manner in which the taxpayer carries on the activity;

- Expertise of the taxpayer or her advisors;

- Time and effort expended by the taxpayer in carrying on the activity;

- Expectation that assets used in the activity may appreciate in value;

- Success of the taxpayer in carrying on other similar or dissimilar activities;

- Taxpayer’s history of income or losses in respect to the activity;

- Amount of occasional profits, if any, which are earned;

- Financial status of the taxpayer; and

- Any elements of personal pleasure or recreation. (xii)

No single factor or even a majority of the factors is controlling, and all of the facts and circumstances must be evaluated, giving greater weight to objective facts than to the taxpayer’s statement of intent. (xiii)

Consider that the IRS can disallow deductions if the activity is deemed a “hobby.” A tax court will likely assess whether the activity (your business) is being carried on in a businesslike manner. Efforts indicating profit objective may include:

- whether accurate books and records are maintained;

- whether personal and horse funds are commingled in personal in bank accounts; and

- the nature and extent of improvements made to grounds and operations. (xiv)

Also consider having a written business plan, track expenses on a per horse basis, and prepare financial projections to assess the economics of the activity.

Employing these tips with the help of a well-versed attorney should help you prepare for the unexpected situation should it arise.

(I) Southern Floors & Acoustics, Inc. v. Max-Yeboah, 267 Va. 682, 687 (2004). See also, (Broaddus v. Standard Drug Co., 211 Va. 645, 649, 179 S.E. 2d 497, 501 (1971); N. & W. Railway v. Johnson, 207 Va. 980, 983-84, 154 S.E. 2d 134, 137 (1967); Smith Adm’r. v. Grenadier,203 Va. 740, 747, 127 S.E. 2d 107, 112 (1962); Ritter Corp v. Rose,200 Va. 736, 742, 107 S.E. 2d 479, 483 (1959) (discussing an exception to this general premise — the legal doctrine of respondeat superior may come into play, if the independent contractor’s torts arise directly out of his use of a dangerous instrumentality, arise out of work that is inherently dangerous, are wrongful per se, are a nuisance, or are such that it would in the natural course of events produce injury unless special precautions were taken).

(ii) McDonald v. Hampton Training School, 254 Va. 79, 81 (1997).

(iii) Id.

(iv) Hernandez v. Industrial Commission, 2008 WL 2410207 (Ariz. App. 2008).

(v) Atkinson v. Sachno, 261 Va. 278, 284 (2001).

(vi) Id. at 284.

(vii) McCotter v. Smithfield Packing Co., 849 F. Supp. 443 (E.D. Va. 1994); see also, Va. Code Ann. § 65.2-307.

(viii) Keating v. Commissioner, 544 F.3d 900 (8th Cir. 2008); 26 U.S.C.S. §§ 162, 212.

(ix) See, 26 U.S.C.S. § 183(a); 26 U.S.C.S. § 183(b).

(x) Treas. Reg. § 1.183-2(a).

(xi) Treas. Reg. § 1.183-2(a).

(xii) Section 1.183-2(b).

(xiii) See, Evans v. Comm’r, 908 F.2d 369, 373 (8th Cir. 1990).

(xiv) See, e.g., Keating, 544 F.3d at 905.

*Photo courtesy of Deanne Cellarosi (dcellarosi.com)

*This article previously appeared on Rate My Horse PRO.